One of the latest additions to my library is the Knox Version of the Bible, published by Baronius Press in 2012. In this unboxing post I’m going to present its features, starting with a brief explainer on this particular translation.

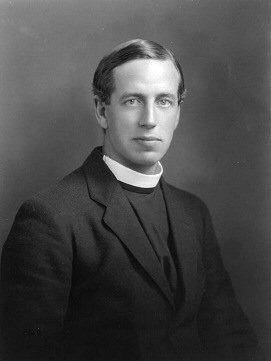

Commonly referred to as the ‘Knox Version’ (KV), this English-language translation of the Bible was first published in the 1940s (the New Testament was released in 1945, with the Old Testament coming out in 1949). The name comes from its sole translator, Msgr. Ronald Knox, an English Catholic priest, scholar and prolific author. He was commissioned by the Roman Catholic Church in 1936 to produce a contemporary Catholic translation that was meant to replace the mid-18th century Douay-Rheims-Challoner version.

Immediately after the WW2 it was in official use by the Catholic Church in the UK for a while, but has since been replaced with other, even more contemporary translations produced by interdenominational committees and large teams of translators and editors. Sadly, it’s currently not included on the list of versions approved for use in the liturgy by the Bishops’s Conference of England and Wales, although it’s still listed as one of the versions that may be used in the Divine Office.

English-speaking readers (Catholic and non-Catholic) are nowadays much more familiar with translations which tend to be based on the Hebrew texts of the Old Testament and the scholarly versions of the Greek New Testament, rather than the Latin Bible (which itself is a translation). The important thing to mention here is that the Knox Bible belongs to the group of translations based on the Latin Vulgate, namely the Clementine Vulgate of 1592, which places it firmly in this more conservative Catholic tradition.

Having said that, the Knox Version has an added benefit, and its full title says it all: The Holy Bible—A Translation From the Latin Vulgate in the Light of the Hebrew and Greek Originals. In other words, while it is based on the Vulgate, Hebrew and Greek manuscripts were also taken into consideration. This is also apparent throughout Knox’ footnotes which are often comments on different readings in the source material and possible textual corruptions and misinterpretations.

(I won’t go into explaining the differences between these two main approaches to choosing the source material, both of which have their advantages and disadvantages. Suffice it to say that, officially speaking, the Roman Catholic Church has long considered the Latin Vulgate, and Vulgate alone, the only inerrant version of the Bible available, which is why many Catholics to this day have a strong preference for translations based solely on it. Hence the enduring popularity of the Douay-Rheims-Challoner among English-speaking Catholics.)

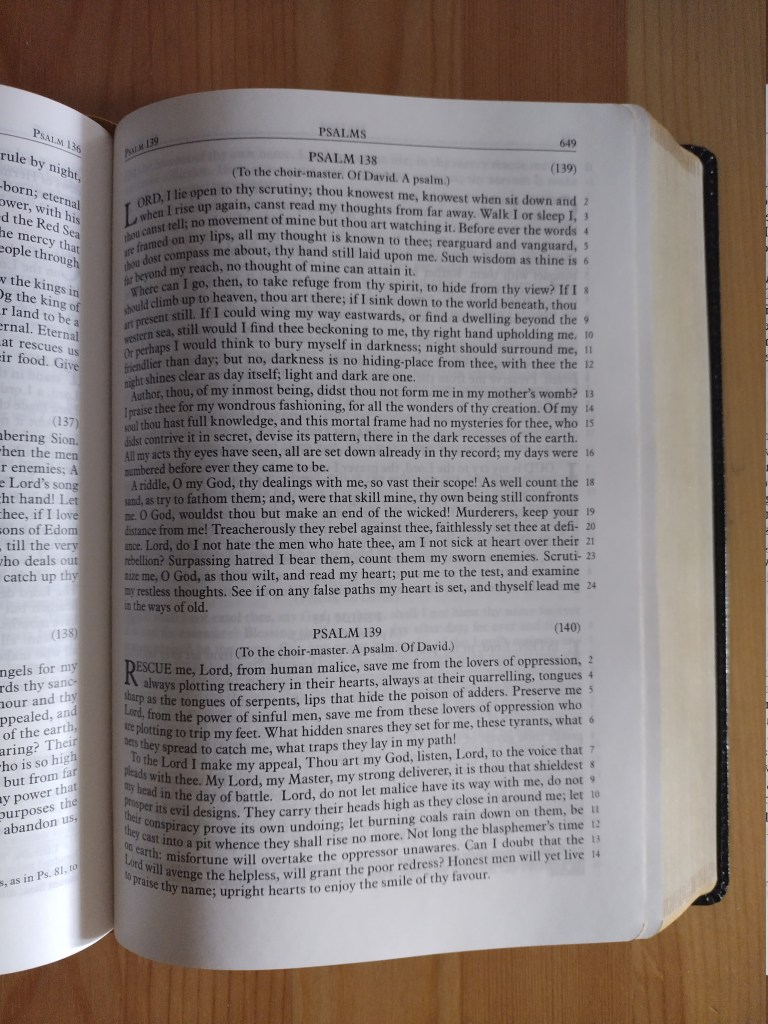

Now, back to the Baronius Press edition of the Knox Bible. As mentioned earlier, it was released in 2012, and it’s a flexible cover, leather bound edition, 6” x 8¼”, with gilded edges. It weighs c. 2.5 lbs and has 1475 pages. It contains Knox’ footnotes with very brief and useful comments on various textual issues and editorial decisions. I am not sure what type of paper was used for this edition; it’s a bit thicker than the standard Bible paper, but in any case, there is very little ghosting and it has a very pleasant scent.

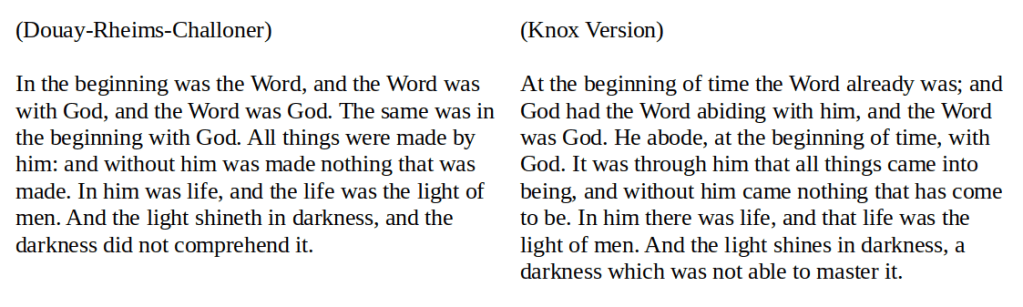

After these formal and technical characteristics, let me comment on the translation itself. Unlike the original Douay-Rheims (and the 18th century Challoner revision), which is a very close and literal translation of the Vulgate, the Knox Version stays true to the original while being stylistically far more polished and nuanced. One can tell that Knox was a fiction writer, among other things, as his translation feels like the work of a wordsmith, and not just a Bible scholar. It’s an interesting combination of literal and dynamic approaches to Bible translation, adopting the best of both worlds. Admittedly, there are verses and passages that do seem rather interpretive, so let’s be clear: this is not a literal translation. But neither is it a paraphrase à la the notorious Message Bible.

Just to get the feel for the style, have a look at these two passages:

Here’s John 1:1-5 (DRC vs KV):

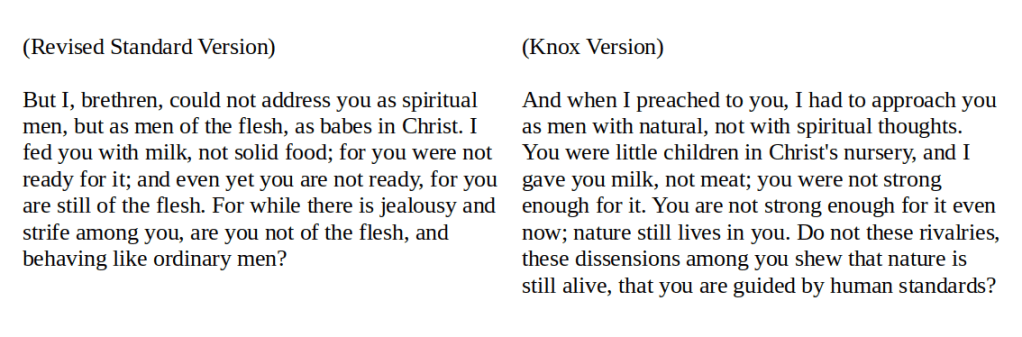

Another sample text, 1 Corinthians 3:1-3 (RSV vs KV):

All of the Knox Version is available online, so you can do a more thorough inspection and compare it against many different translations.

On the whole, the Knox Version does have an old-fashioned feel to it, but very different from the Douay-Rheims-Challoner, which is often burdened with weird syntax and awkward choice of vocabulary (not to mention its heavy reliance on the King James Version). Compared to other translations, it feels very elegant and sophisticated. It’s a trustworthy translation of the Vulgate that doesn’t suffer from the stylistic deficiencies of the Douay-Rheims-Challoner or some of the popular modern translations which can sound very bland and flat. For the purposes of Bible study, I would suggest using the Douay-Rheims-Challoner and the Knox Version together, since the Douay-Rheims-Challoner closely follows the Latin Vulgate, while the Knox Version presents a contemporary yet timeless, classical and very stylish translation.

If you haven’t used this version before, do give it a chance—you won’t regret it.

Discover more from grammaticus

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.